Should We Stretch the Upper Traps ... or not?

“I try to stretch my shoulders all the time, but it doesn’t seem to work – they are just so tight!”

This is what many people say when they arrive for their massage.

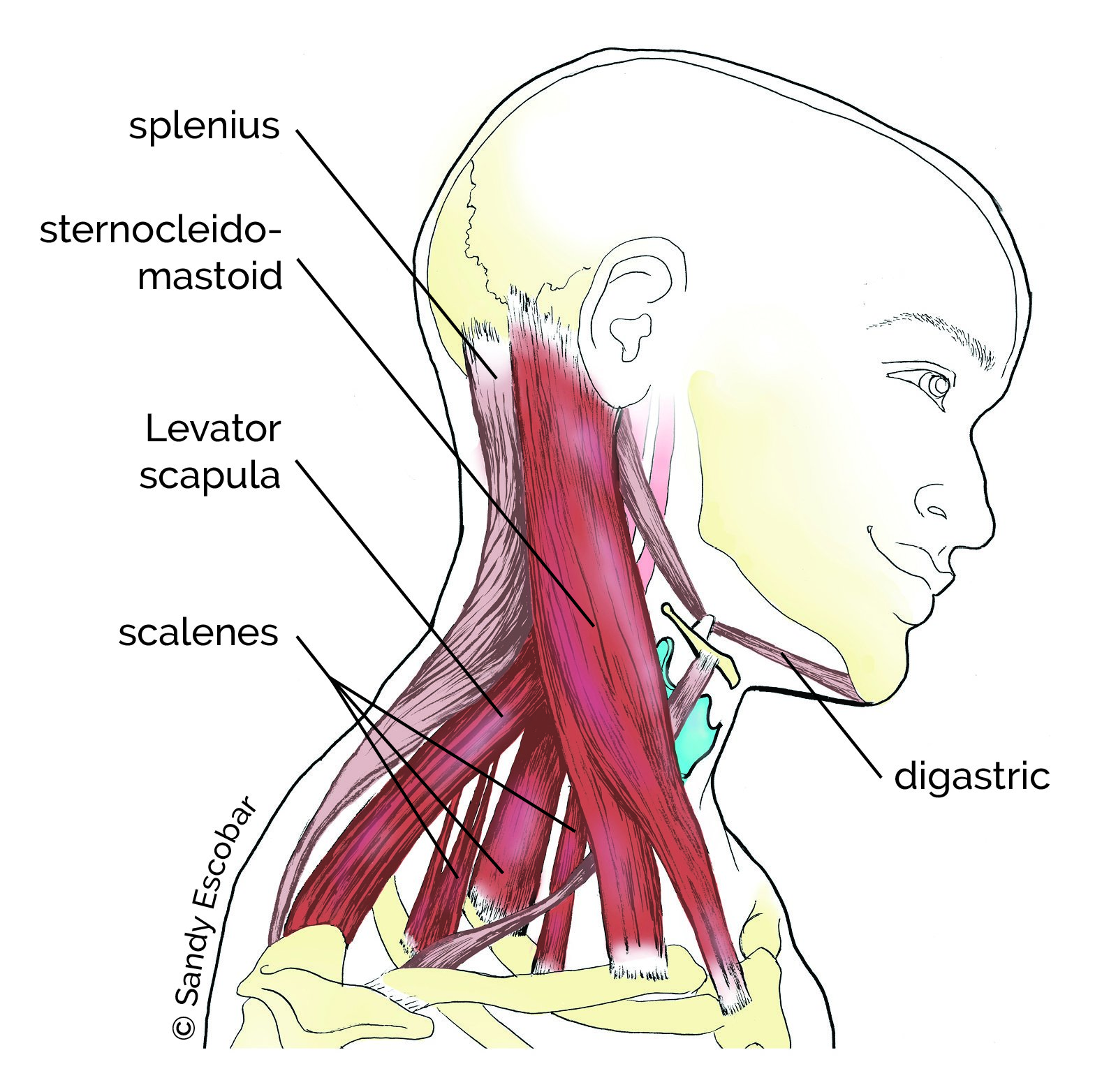

We are taught to stretch those tight muscles on top of the shoulders and the sides of the neck. These muscles include Upper Trapezius, Levator Scapula, SCM, Splenius Capitis and Cervicis, and the Scalenes.

Well-meaning yoga teachers and exercise trainers tell us to do the ear-to-shoulder stretch – sometimes by pressing down on the side of the head to ‘deepen’ the stretch. In fact, I have just seen this very stretch promoted in a popular massage magazine.

We stretch these muscles, yet it doesn’t seem to work. Why is that?

I believe it’s not only unnecessary to stretch, but harmful if you are trying to relieve tension in these tissues.

Let’s take a closer look at the Why.

Each muscle has a certain range that it is comfortable with, as far as stretching and loading. Generally, the weaker the muscle the smaller is its range.

For example, your upper trapezius is able to extend to a certain point until it begins to fight the extension, i.e. resist the stretch, in order to protect itself. This is known as “Neural Inhibition” – our body’s natural mechanism of protecting itself from further damage – so we don’t hurt ourselves when we don’t pay attention.

Thanks to neural inhibition, our muscles contract when they are stretched beyond their end point. This way they will not tear. This makes sense, right?

Yes, it’s common sense. However, we seem to ignore this very basic concept when we stretch our neck and shoulders.

During the day, our upper traps, levators, and other muscles in the neck and shoulders are pulled down – they support our arms, which hang down most of the day. When driving, sitting at computer or sitting down to eat, running or hiking, biking or taking a stroll, most of the time, those muscles are pulled down and basically stretched taut to their maximum end point.

After a while, a few hours of being stretched taut, all of these muscles start to contract to protect themselves from over-tearing. As they contract, they ‘feel’ tight because the sensation of contracting is the sensation of tightening. Unfortunately, we mistake this sensation for tension that needs to be stretched. So we force them back into its maximum stretched-out position.

Finally, the muscles are not able to handle this over-stretching, and they tear – tiny microscopic tears, which heal with collagen fibers.

The next day, this process repeats: The shoulder muscles are pulled down all day without relief, we misinterpret the sensation of over-protection for tension, and …. we stretch them! And of course, more microscopic tears occur. And again, and again.

Over time, this becomes a pattern. The buildup of collagen, now a scar tissue, palpable and often visible, aka the crunchy spot, aches and bothers us non-stop.

So let me pose this initial question one more time.

Do you think we need to stretch our neck and shoulders?

By now, the answer should be obvious…. No!

Then what to do?

Well, for starters, stop stretching them.

Second, simply reverse your pattern of “arms down” to the pattern of “arms up” as often as 3-4 times daily. This will give these muscles a needed break, and hopefully relieve some tension buildup.

What is the “arms up” pattern?

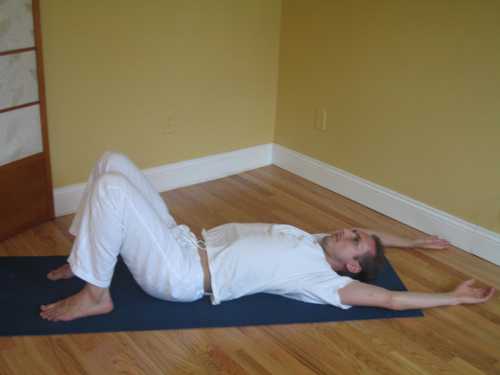

Any position, where your arms are raised up alongside your ears:

- lying down on your back and resting (knees bent or straight) with arms up;

- hanging on a horizontal bar, or even just hooking your fingers on a door frame for a few breaths;

- forward-bending and letting the arms hang loose for a minute;

- taking the Child’s pose (from yoga), and resting in it for a minute.

Some or all of these poses should be practiced if you experience the crunchy spots, achy-ness, regular tension, sharp and ‘shooting’ nerve sensations in your shoulders and neck.

Why do these positions work?

Because they slack those over-stretched muscles, they give them a break.

What else can we do instead of stretching?

The best thing to do for any muscle is to keep it strong. Strength is the long-term solution.

Strong muscles do not tire easily and are able to sustain longer loading.

Second best, or perhaps as important as strength, is to apply pressure to the affected muscles to relieve tension.

Pressure should be applied on a regular basis to all the problematic areas with the intention of soothing and ‘smoothing out’ the stringy, knotty, crunchy spots so they do not have a chance to become chronic.

Contact Slava if you'd like to try his Neuro-Musculo-Skeletal Bodywork.